The Mughal Empire (1526–1858) was a decisive period in South Asian history, known for its meteoric rise as a military and cultural force and its long fall under native discord and colonial rule. Established in 1526, the empire experienced a golden age under its rulers Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, but finally fell apart after Aurangzeb’s death (1707) and finally formally ended after the 1857 Rebellion. This paper presents an overview of its course in three periods: the rise & establishment (1526–1556), the peak in the golden age (1556–1707), the decline & fall (1707–1858). Drawing on primary sources like the Baburnama and Akbarnama and economic estimates from historians like Shireen Moosvi and J. F. Richards, it examines the dynamics of military innovation, governance, cultural synthesis, and economic trends that governed its history. Particular attention is devoted to revenue data and the logistics of the 1857 uprising, throwing light on the empire’s economic collapse and last-ditch resistance.

Origins and Establishment (1526–1556)

Babur’s lineage ran back to Timur on his father’s side and Genghis Khan through his mother, giving him a heritage of conquest. Born in 1483 in the Ferghana Valley (now in modern Uzbekistan), he inherited a small principality at the age of 12 but lost it in rivalries between Timurid princes. His early career was an unceasing effort to retake Samarkand, Timur’s capital, which he captured for brief periods (1497, 1501, 1511) only to be expelled by Uzbeks under Shaybani Khan. By 1519, Babur turned his attention to the southeast, conquering Kabul in 1504 and making it a springboard for his conquest of Hindustan’s wealth. His Baburnama, a voluble memoir, lays bare a restless warrior-prince propelled by desperate need and fatalism: “I had no hope left in anyone… I turned my face toward Kabul” (Babur trans. Thackston, 1996, p. 189). This major shift was the prelude to his Indian venture.

The Conquest of Northern India (1526–1530)

Babur’s invasion of India was on the invitation of disgruntled nobility of the Delhi Sultanate led by Daulat Khan Lodi who wanted to remove Sultan Ibrahim Lodi. The First Battle of Panipat took place on April 21, 1526 where Babur encountered Lodi’s numerically superior army, estimated to be 100,000 men and 100 elephants strong. Babur made do with around 12,000 troops, employing tactical skill, utilizing matchlock muskets, field artillery, and a defensive wagon-line (araba) inspired by Ottoman methods. This technological advantage, along with disciplined cavalry charges, decimated Lodi’s forces, killing the sultan and sealing Delhi. By God’s grace, this difficult affair was made easy,” the Baburnama notes (p. 328), reminding us of Babur’s use of gunpowder, an innovation in Indian warfare.

The battle at Panipat was merely the first step. At the Battle of Khanwa in 1527, the Rajput confederacy led by Rana Sanga of Mewar was a formidable opponent for Babur. Outnumbered, Babur’s artillery and his morale-boosting promise to forgo alcohol (a symbolic act chronicled in his memoirs) sealed yet another victory, neutralizing Rajput opposition. His consolidation on the Ganges plain was further consolidated by the battle of Ghaghra (1529) against eastern Afghan chiefs. When he died in 1530, Babur ruled a fledgling empire that extended from Kabul to Bihar, but its frontiers were still fluid. Iranshahis rule bequeathed Persianate governance—land revenue systems, courtly formalities—and a cultural bedrock for successors.

Humayun’s Trials and Exile (1530–1555)

At age 22, Babur’s son Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad Humayun inherited a tenuous realm. Lacking his father’s decisiveness, Humayun confronted immediate challenges: recalcitrant Afghan nobles; wily brothers (Kamran, Askari and Hindal); and the ascendance of Sher Shah Suri, a formidable Afghan usurper. Sher Shah (a former governor under the Lodis) took advantage of the Mughal disorder and defeated Humayun at the Battle of Chausa (1539) and Kannauj (1540). These losses drove Humayun into 15 years of exile, first to Sindh and Rajasthan, then to the Safavid court of Shah Tahmasp in Persia seeking refuge. The Safavids, seeking a way to push back against the Sunni Uzbeks, offered Humayun 12,000 soldiers in return for his temporary conversion to Shia Islam and the handover of Kandahar (a contentious issue with his brother Kamran).

Humayun’s exile was a transformative experience. Exposure to Safavid military organization — especially artillery and cavalry tactics — enhanced his abilities. He re-entered Kabul after taking it from Kamran in 1545, and by 1555 he took advantage of what followed Sher Shah’s death (1545) and the weak rule of his successors. In June 1555, with Persian support, Humayun overcame Sikandar Suri at Sirhind, recovering Delhi. His rehabilitation was brief; he died in January 1556 after falling from the stairs of his library, leaving the empire to his 13-year-old son, Akbar.

Analysis and Significance

The Mughal Empires Origins: A Mix of Opportunism and Resilience Babur’s new military technologies—notably in gunpowder and mobility—overcame numerical disparity to win a foothold that upended Indian polities based in fragmentation. But his untimely death — and Humayun’s failures — revealed the empire’s fragility, dependent on individual élan rather than institutional solidity. Sher Shah’s 1540-1555 interlude threw up the reforms—the standardized currency, the road networks (Grand Trunk Road)—that the Mughals later adopted, and illustrates a dynamic exchange of power. Humayun’s Persian stay, in turn, intensified the empire’s cultural and military connections with Safavid world, a legacy visible in Mughal art and warfare.

The Golden Age (1556–1707)

The golden age of the Mughal Empire (1556 to 1707), was a time when Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb transformed the Indian polity into a centralized, culturally vibrant empire, each leaving a legacy of his own.

Akbar the Great (1556–1605).

Ruler Culture, Religion and War under Akbar the Grea

THE STORY OF AKBAR THE GREAT: Mughal emperors ruled over a vast empire in the Indian subcontinent from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. His rule epitomised the consolidation of Mughal sovereignty in the Indian subcontinent, wherein Persian imperial traditions intermingled with autochthonous Indian strands to forge a distinct – even don words– ruler culture. Akbar’s policies on religion and warfare were radical for his time, embodying a pragmatic yet visionary approach in which he balanced conquest with coexistence. This essay shows how Akbar’s ruler culture, his visionary religious policies, and his military campaigns came together in an entangled legacy of tolerance, administrative brilliance and imperial expansion.

Ruler Culture: The Making of a Mughal Sovereign

After his father, Humayun, died in 1556, Akbar became ruler at the young age of 13. His early life spent under the regency of Bairam Khan was steeped in the Persianate traditions inherited from his Timurid ancestors, not least from Babur, the Mughal dynasty’s founder. But the ruler’s culture in Akbar’s own time turned out to be a uniquely syncretic one, befitting his ambition to preside over an empire that included Hindus, Muslims, Jains, Sikhs and others.

At the heart of Akbar’s ruler culture was sulh-i-kul, or “universal tolerance,” which became the bedrock of his governance. Unlike his predecessors, who were typically conquerors ruling in strict conformance with Islamic strictures, Akbar presented himself as a paternal figure — a ruler of all subjects, regardless of faith or ethnicity. This represented a profound break with the typical coarseness of Islamic rulers at the time, who generally promoted ummah (the Muslim community) supremacy. Akbar’s court at Fatehpur Sikri, Agra and Lahore was a melting pot of ideas bringing poets, philosophers, artists and theologians from different backgrounds together.

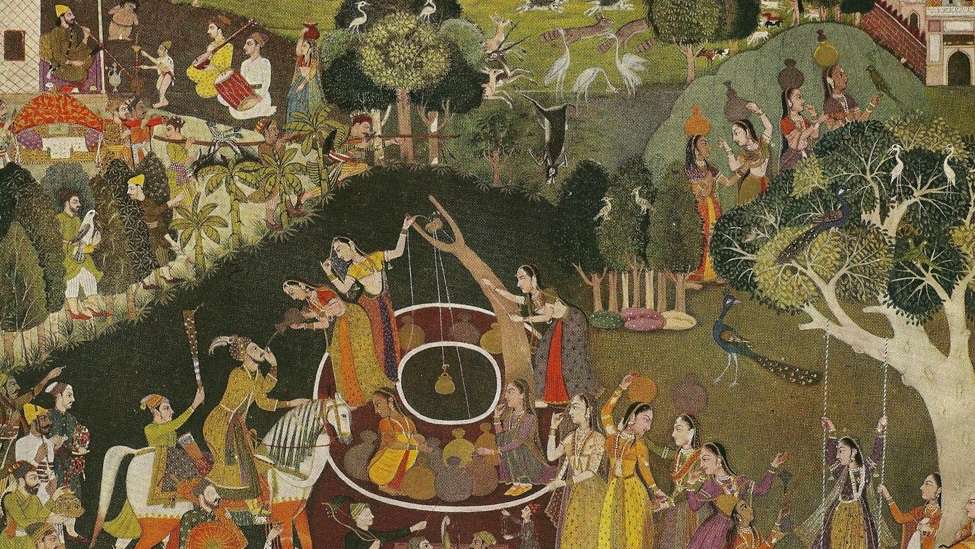

Akbar's Mughal court was a scene of unimaginable grandeur and sophistication. He also adopted the Persian practice of darbar (court assemblies), in which he received petitions, delivered justice and exhibited his power through elaborate rituals. His patronage of the arts — as seen in the illuminated pages of the Akbarnama (an account of his reign by Abul Fazl) and in miniature paintings — was part of a ruler culture that exalted both martial valor and intellectual endeavor. Akbar’s hands-on involvement in these projects, including commissioning translations of Sanskrit texts like the Mahabharata into Persian, underscored his eagerness to transcend religious and cultural boundaries.

Akbar also redefined the Mughal nobility, assimilating Rajput chieftains into his administration with marriage alliances and military roles. His marriages with Rajput princesses, like Harka Bai (later, Mariam-uz-Zamani), represented this synthesis and gave legitimacy to his rule among Hindu subjects. Such ruler-culture inclusiveness was not simply performative; it was a strategic way of ensuring stability in an empire that had regional loyalties.

To be Continued........

<img src ='https://cms.thepapyrusbd.com/public/storage/inside-article-image/e2fn2j4ni.jpg'>

Comments