Religion: A Policy of Syncretism and Disagreement

The religious beliefs of Akbar existed beyond strict doctrinal rules as an ongoing exploratory field which sought peaceful integration between faiths. At his birth Akbar inherited the status of Sunni Muslim in a governing empire composed mostly of Hindu subjects. At the beginning of his rule he upheld traditional Islamic teachings before a global religious crisis together with his intellectual nature made him initiate a complete shift. The House of Worship at Fatehpur Sikri represents one of the most significant contributions that Akbar made to the world in 1575.

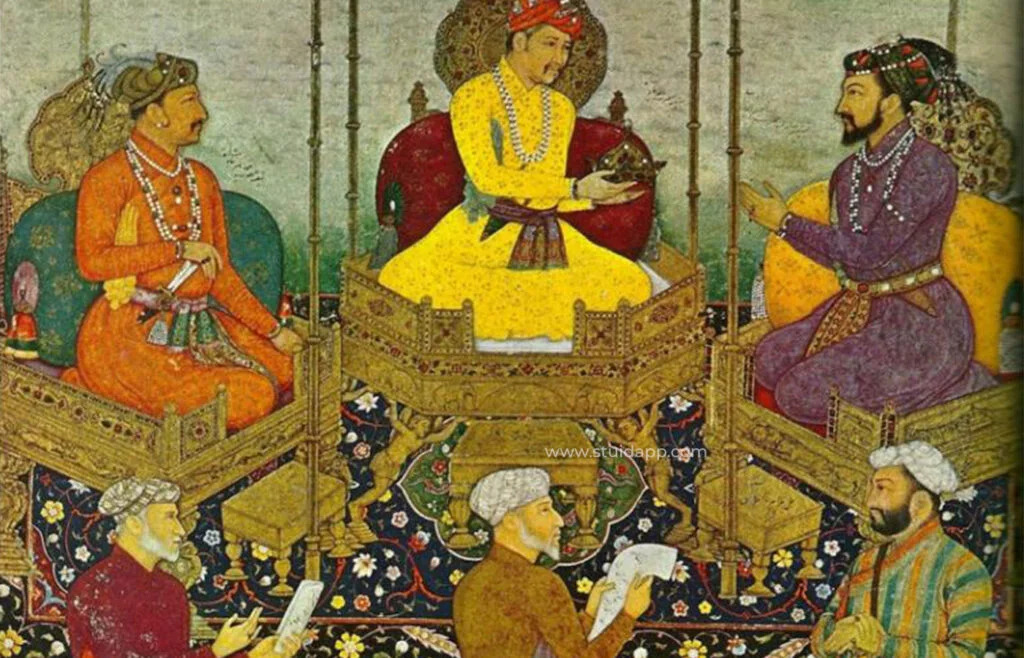

The Muslim theological gathering site expanded rapidly to include discussions about creeds and religion between Muslim scholars and Hindu, Jain and Zoroastrian and Christ followers and Jesuit missionaries from Goa. Through those discussions Akbar recognized what proved to be the collapse of blind faith and the global outlook. Akbar became discontented with the Islamic scholars' (ulema) religious disputes to the point where he would ultimately discard their position because he wanted to overcome religious divisions. Akbar established Din-i-Illahi (Divine Faith) in 1582 by integrating elements of Islam with Hinduism and Jainism and Zoroastrianism. Under this new system ethical values such as devotion to the emperor and harmlessness toward both spiritual teachings superseded ritualistic belief systems.

Historians disagree regarding the Din-i-Ilahi status while some argue Akbar founded a new faith yet most experts classify it as a philosophical order which had Akbar as its religious leader. Little success marked its acceptance by popular audiences because those closest to Akbar like Birbal and Abul Fazl became its formal adherents while most other people rejected it indicating the divinity-focused nature of this movement rather than its status as a widespread movement. The religious policies established by Akbar had specific functional results.

During 1564, he eliminated the jizya tax which reduced non-Muslim financial obligations thus exemplifying his dedication to social equality. The religious policies of Akbar brought favorable relations with all non-Muslim subjects because he both banned forced conversions and sanctioned temple construction. The new religious policies of Akbar provoked Sunnis to accuse him of committing apostasy against their traditional beliefs. Akbar responded by strengthening his control while disempowering the uluema and establishing a divine monarch ruling as the Persian concept farr-i-izadi or divine effulgence.

Behind his tolerant practices regarding other faiths Akbar experienced significant internal religious pressure. The policies implemented by Akbar successfully inhibited major religion wars across his territories yet his approach generated dissension among traditionalist circles within his realm that blossomed during the rule of Aurangzeb. Through dialog and not through repression Akbar managed diverse elements of his kingdom thus achieving almost complete avoidance of interfaith conflict during his administration.

The Muslim theological gathering site expanded rapidly to include discussions about creeds and religion between Muslim scholars and Hindu, Jain, and Zoroastrian and Christ followers and Jesuit missionaries from Goa. Through those discussions, Akbar recognized what proved to be the collapse of blind faith and the global outlook. Akbar became discontented with the Islamic scholars' (ulema) religious disputes to the point where he would ultimately discard their position because he wanted to overcome religious divisions. Akbar established Din-i-Illahi (Divine Faith) in 1582 by integrating elements of Islam with Hinduism, Jainism, and Zoroastrianism. Under this new system, ethical values such as devotion to the emperor and harmlessness toward both spiritual teachings superseded ritualistic belief systems.

Historians disagree regarding the Din-i-Ilahi status, while some argue Akbar founded a new faith, yet most experts classify it as a philosophical order that had Akbar as its religious leader. Little success marked its acceptance by popular audiences because those closest to Akbar, like Birbal and Abul Fazl, became its formal adherents while most other people rejected it, indicating the divinity-focused nature of this movement rather than its status as a widespread movement. The religious policies established by Akbar had specific functional results.

During 1564, he eliminated the jizya tax, which reduced non-Muslim financial obligations thus exemplifying his dedication to social equality. The religious policies of Akbar brought favorable relations with all non-Muslim subjects because he both banned forced conversions and sanctioned temple construction. The new religious policies of Akbar provoked Sunnis to accuse him of committing apostasy against their traditional beliefs. Akbar responded by strengthening his control while disempowering the uluema and establishing a divine monarch ruling as the Persian concept farr-i-izadi, or divine effulgence.

Behind his tolerant practices regarding other faiths, Akbar experienced significant internal religious pressure. The policies implemented by Akbar successfully inhibited major religion wars across his territories, yet his approach generated dissension among traditionalist circles within his realm that blossomed during the rule of Aurangzeb. Through dialog and not through repression, Akbar managed diverse elements of his kingdom, thus achieving almost complete avoidance of interfaith conflict during his administration.

War: Conquer and Consolidate

Warfare was the fulcrum of Akbar’s empire-building, but his military campaigns were as much an exercise in diplomacy as they were in conquest. Under his rule the Mughal empire grew from a tenuous dominion in northern India to a broad empire from Gujarat in the west to Bengal in the east, and Kashmir in the north to the Deccan in the south.

Bairam Khan, a trusted military commander earlier in Akbar’s reign, led the way in Akbar’s early military victories, including the Second Battle of Panipat (1556), which helped to cement his hold on the throne against the Sur dynasty’s Hemu. The Rajput kingdoms presented both a political and cultural challenge to Akbar, who took direct control of the Mughal Empire in 1560, and began a series of campaigns to bring them to heel. The siege of Chittorgarh (1567–68) was a brutal show of Mughal power, concluding with a massacre once Rajput defenders refused to surrender. But Akbar went on to present a conciliatory face, seeking alliances with surviving Rajput clans, such as the Kachwahas and Sisodias, and bringing them into his empire, instead of destroying them.

The conquest of Gujarat (1572–73) and Bengal (1574–76) opened another chapter in Akbar’s strategic intelligence. Gujarat’s ports yielded wealth and maritime access; Bengal’s plenteous lands made the resources of the empire pop. These campaigns depended on a well-organized army, which included cavalry, artillery (particularly cannons), and war elephants, further backed up by a logistics network that enabled travel over many types of landscape.

Akbar’s military culture was built on loyalty and merit. He implemented the mansabdari system, a hierarchal organization in which the nobility (known as mansabdars) were classified according to the size of their armies and granted jagirs (land grants). This system guaranteed a regular supply of soldiers and shackled the nobility to the emperor’s service. Unlike earlier rulers, who governed with the support of tribal levies, Akbar’s army was a professional one, combining Persian, Turkic and Indian martial traditions.

Akbar’s wars were broad, but not fueled by passion for a religion. Unlike the Ghaznavids or earlier Delhi sultans, who framed their conquests as jihad, Akbar’s campaigns were political unification. His dealings with many vanquished adversaries offered them terms of honorable surrender rather than summary execution, a ruling class ethos that prioritized stability over vengeance. For instance, Akbar conquered Malwa and its ruler Baz Bahadur but regranted him as a vassal, something he continued to do with many Rajput kings.

The Deccan campaigns in Akbar’s later years (1590s) stretched the military limits of his empire. The sultanates of Ahmadnagar, Bijapur and Golconda resisted Mughal hegemony, and though Akbar made some territorial inroads — he captured Ahmadnagar in 1600 — this conquest was an incomplete one, and a warning of troubles to come for his successors. Still, his ability to reach out in force in southern India cemented the claim of the Mughals as an all-India empire.

War, Culture, and Religion in the Crosshairs

Akbar’s culture of rule, religious policies, and military efforts were intricately linked. Inclusion in governance preempted potential rebellions, enabling him to concentrate resources on external conquests. By marrying into Rajput families and abolishing discriminatory taxes, he won the loyalty of Hindu warriors, who became an essential part of his armies. This melding of religions allowed for victories such as at Ranthambore (1569) and served to keep the empire together.

Humanely, Akbar’s tolerance spared India sectarian wars that ravaged contemporary Europe (such as the Thirty Years’ War). His debates in the Ibadat Khana and the Din-i-Ilahi were a series of intellectual exercises that mirrored his battlefield pragmatism — both sought to unify rather than divide. Militarily, his wars expanded the spread of the empire’s foothold, but it was his diplomatic finesse that ensured these gains were sustainable, as evidenced by the deep-rooted Rajput alliances.

Legacy

Akbar the Great’s rule, a golden age of Mughal rule, was characterized by a culture of ruling with plurality, a religious policy that resisted orthodoxy and a military strategy that as-much focused on diplomatic techniques as it did on use-of-force. His empire was more than a mere territory but a civilizational experiment, when Persianate traditions collided with Indian realities. While his successors found it hard to strike this balance — Jahangir with his fondness for artistry, Shah Jahan for grandeur, Aurangzeb for orthodoxy — Akbar’s model of governance made a permanent imprint on Indian history.

Jahangir (1605–1627)

Jahangir: Culture, Religion, and War of the Emperor

Jahangir, then called Salim, was the son of Akbar the Great and came to the Mughal throne in 1605 after the death of his father. His reign, which lasted 22 years, is widely regarded as one of consolidation rather than expansion: the establishment that Akbar laid down was fortified under his supervision. Jahangir’s culture of rulership had something of Persianate sophistication, personal eccentricity and a profound sense of the aesthetic, and his attitude toward religion had something of Akbar’s continuing tolerance but less intellectual ardor. His military campaigns, if less ambitious than his father’s, were crucial to maintaining Mughal supremacy. This essay explores these three dimensions, the culture of rule and also religion and war, and through them continue to show how Jahangir exercised his tenets of empire.

Ruler Culture: The Emperor’s New Aesthetic

The culture of Jahangir’s rule was an inheritance of the Mughal culture of grandeur, but came packaged with Jahangir’s own sensibilities as an admirer of beauty and a ruler drunk on the pleasures of power. His full name, Nur-ud-Din Muhammad Jahangir, "Light of the Faith" and "Conqueror of the World," spoke to the great ideals he had inherited, but his rule was more about cultivation than conquest. Unlike Akbar, who pursued a revolutionary agenda that was central to his conception of his court as a center of political and intellectual innovation, Jahangir’s court was a stage for the demonstration of artistic expression and individual authority.

Emperors still held elaborate rituals that confirmed their sovereignty, but the Mughal darbar of Jahangir also maintained its ceremonial splendor. Among his most famed innovations was the Zanjir-i-Adl (Chain of Justice), a golden chain with bells strung outside his Agra palace, enabling any subject to petition him directly. Although its effectiveness is questioned, it represented Jahangir’s wish to present himself as a just king, approachable by the commonalty — an allusion to Akbar’s paternalistic politics, yet theatrical.

Jahangir’s culture of rulership was intimately connected to the arts. His sponsorship of miniature painting was at its peak, with artists like Ustad Mansur producing masterpieces that conveyed the natural world — plant life, animals, portraits — in unprecedented realism. His Persian memoir, the Jahangirnama, provides a glimpse of his character: self-critical, boastful, obsessed with detail, whether he was writing about a rare bird or his own edicts. This was a personal project: Akbar’s was a commissioned Akbarnama, while Jahangir’s own account reflects that same self-absorbed impulse that made him want to tell his own story.

His court became a cosmopolitan meeting ground, with Persian poets, European travelers (most famously, Sir Thomas Roe, the English ambassador) and Indian nobles. A paragon of the world-historical man, Jahangir’s fascination with the West comes through his dealings with the English, who he allowed trading rights in 1615—a practical decision that foreshadowed centuries of European influence in India. His marriage to the Persian noblewoman Nur Jahan also elevated that culture. Nur Jahan’s influence was immense; she stood behind the throne, minting coins in her name, shaping policy, making Jahangir’s reign an unusual case of shared rulership in the history of the Mughals.

Jahangir’s personal pleasures — his fondness for wine, opium and extravagance — were also the substance of his indolent ruler culture. Though these traits made for a more relatable figure in his memoirs, they sometimes diminished his authority, especially when dealing with rebellions led by his son Khusrau and, later, Shah Jahan. But his willingness to delegate to capable administrators like Nur Jahan and her brother Asaf Khan ensured the stability of the empire, revealing a ruler culture that balanced personal pleasure with political acumen.

Religion: Acknowledging Continuity with a Personal Twist

Jahangir inherited the Mughal policy of sulh-i-kul (peace with all) of Akbar, but his own attitude towards religion was less reformed and more pragmatic. The court he grew up in was culturally rich and diverse, and Jahangir remained secular, steering clear of the religious wars that beset many other empires of the time. During his reign, he faced no significant internal wars fueled by religion, a mark of Akbar’s system, which would endure to this day.

Unlike Akbar, who actively participated in religious discourses and developed the Din-i-Ilahi, Jahangir did not seem to have any intention of forming a new order of faith. He kept interacting with various religious communities, giving audiences to Hindu ascetics, Jain monks and Christian missionaries. His memoirs tell of encounters with Jadrup, a Hindu yogi, who fascinated him for his asceticism, suggesting that he had a personal interest in spirituality but not a systematic policy toward it. Likewise, his dealings with Jesuit priests, recorded by European travelers, indicate a monarch fascinated by Christianity but disinclined to embrace it.

There were limits to Jahangir’s tolerance, though. So, early in his reign, he confronted a rebellion by his son Khusrau (1605–06), backed by orthodox Muslim groups opposed to Akbar’s legacy. In retaliation, the fifth Sikh Guru, Guru Arjan Dev, was executed by Jahangir in 1606 on charges of sympathizing with Khusrau. Although politically motivated, this action sorely tested relations with this growing community and represented an aberration in Jahangir as a case of religious persecution. He later made peace with the Sikhs, but the episode shows a pragmatic streak: To him, religion was a means to keep order, not an ideological battlefield.

Nur Jahan also had a role in religious policy. In a Sunni-dominated court, she emphasized harmony as a Shia Muslim who created an atmosphere in which sectarian divides were brushed aside. The couple’s deference to Sufi shrines, like the one run by Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer, was also a continuation of the Mughal tradition of backing what is sometimes called mystical Islam, which has had an attraction across communities. Jahangir’s reign therefore escaped “religion wars” not by bold innovation but by maintaining a fragile balance reliant on the goodwill Akbar had instilled.

Orthodox ulema objected from time to time to Jahangir’s laxity — his drinking and unorthodox manner in the court did not conform to Islamic injunctions — but he did manage to keep them at bay, much as Akbar did. His empire was not about winning over adherents of the faith, but rather about perpetuating a multifaith empire through a disinterest in dogma and a concern for loyalty to the throne.

Comments